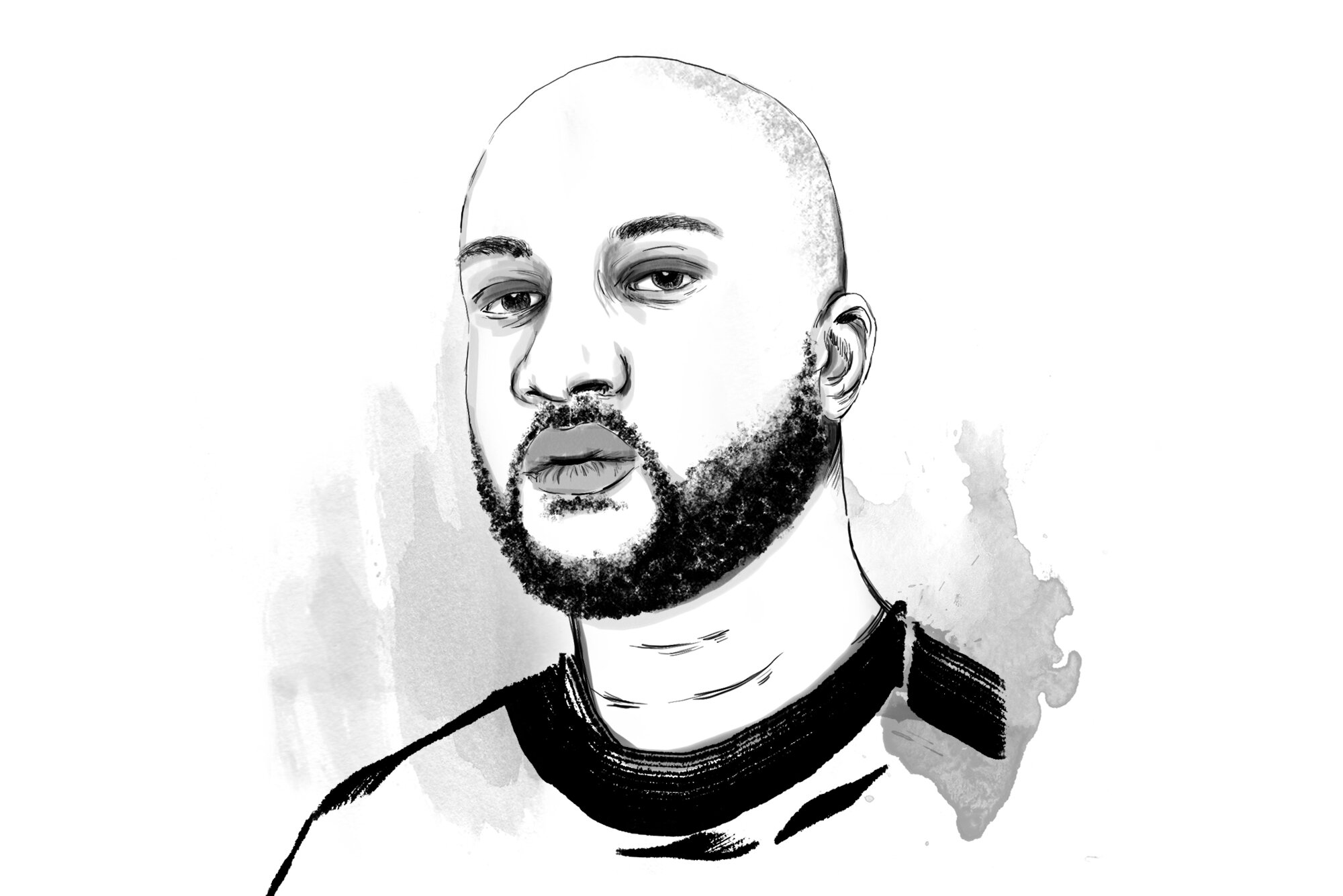

Virgil Abloh

Virgil Abloh is a man of many talents.

Since a young age, the designer-cum-creative director has worked on a multitude of projects from art installations, hotels and fashion collaborations to designing furniture and DJing. Top of this ever-growing list is the gig that placed him at the centre of pop culture in the first place – his role as Kanye West’s long-time consultant and creative director. Most recently, however, he has caught the attention of the fashion industry with his label Off -White which he launched in 2013.

We sat down with Virgil to talk about his vision for Off-White, the youth culture he inspires and the legacy he wants to leave behind.

You studied engineering and architecture – when did fashion come into the picture?

Ironically I studied architecture not to necessarily practice it – I thought it was a good base education to do other things. From the start, I wanted more than one career, but it was a good foundation to understand how design relates to culture and the cities around it.

Your real fashion education started when you interned at Fendi. What did you learn?

The importance of product versus the brand and how they relate to each other. It started to understand why things are deemed luxury, commercial, high fashion or high street. Being in tune with that is the first part to building brand, then making design decisions in response to that is the second part.

Why did you start Off-White?

There are ideas in art that generally don’t have a place in fashion. There’s Warhol the work, then there’s the theology behind the work. It has a heightened value because it’s embraced by culture which puts it on a certain pedestal. It’s the same with Off-White – that’s how its designed and made. It relates to younger people but has a different sensibility that uses things from classic luxury to stand on. That’s where the name comes from – it sits in its own world, in between black and white.

Customers at the end of the day are looking for a brand, not clothing. You’ve had clothes since you were born, but the only reason you shop is because you are looking for something beyond that. You wear a brand to reflect who you are. Clothing that exists on streets is like this – you aren’t buying it for utility, it’s for the name, or to add to your personality so when someone sees you they can understand what’s beneath. Branding is what you are making, clothing is the means to an end.

Why did you decide to position the brand within the luxury realm?

In the space of true contemporary clothing there is no room for ideas. People buy clothes to buy clothes. This is completely different to say designer clothing – I look at it like art. You can buy art anywhere but if you buy it from a person who has a specific feel and is making something a specific way, it’s exciting.

Off-White Spring/Summer 2017

You talk about Off-White representing the youth culture, but yet most of this generation can’t afford your clothes…

I think it’s a misnomer, or misinterpreted that I am just about youth culture. To me what I do is not streetwear, it’s a term people choose to use to describe the brand. I’m very close to say a brand like Supreme in ethos and energy, but it is streetwear whereas we are not. Streetwear is essentially a 30-dollar market while my clothes are made in factories that are making brands like Brunello Cucinelli.

It annoys me because when high fashion makes a reference to a rock n roll T-shirt, it doesn’t get labelled as streetwear, but it’s deemed as a designer dipping into youth culture. Yet when I do it, it gets categorised immediately. People don’t understand that I’ve existed in this youth culture for 14 years. It’s a culture most designers peer into, place on a moodboard and then design from. You have two ways of existing – you can pretend to be someone you’re not to fit in, or you can embrace what made you, your point of view and insert this into the market. I’ve done the second.

You’ve been quoted saying that you don’t care if Off-White makes money…

Yes, I don’t consider the bottom line of the brand. I built this brand to value relevance over revenue. It’s may be an artistic thing to say, but if it all disappeared tomorrow, it doesn’t take away anything. Off-White exists as part of a theory I have. If you design a fashion business just for revenue you are going to get the same thing as everyone else on the street. I am more interested in being relevant or having a reason to exist.

What brands do you aspire to be like?

Each brand has its own metric for existing. I love most brands for different things. Not all of them have to be a reflection of the time. My favourite brand is Chrome Hearts actually. I have an infinity of brands where you can feel that one person has designed it, from the pen to the hinge on door to the clothes. You can feel a real strictness there, it’s not about the tangible.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago will be unveiling a retrospective of your work in 2019. Tell us a bit about it.

There is a lot of thoughts behind how I got here and the museum recognised that there’s something deeper behind how I came to be. If you focus on the brand that’s interesting but we intend to look at the 950 projects I have done to then reflect on what it says about the millennial culture. What does all that stuff mean about a generation of kids that were no longer marketed to, and that started using their own ideas to make things? Adding social media to the mix has meant that niche cultures are no longer a niche. It’s continual thread of not just how I think but how a generation thinks.

How do you stay relevant?

Travel, talk to people, participate in culture. Don’t sit in an office looking at images and rely on your staff to give you inspiration. I create based on reaction. When I see a trend I absorb it, and put something in that stream.

What legacy do you want to leave behind?

I haven’t thought about it, because I’m too busy creating. I would love to steer a legacy house. Anything I do is a way to expel my creative energy. I don’t have a young revolutionary approach to fashion, I love the in between, I think it’s important.

A version of this interview first appeared in the South China Morning Post newspaper.